When we talk about “keto-adaptation” we seem to be talking about one process but there are really several. The HPA axis in the brain has to adapt. The muscles have to adapt. The astrocytes have to adapt. The liver has to adapt. The gut has to adapt. The adipose layer itself has to adapt. And the pancreas has to adapt. Biodiversity, genetics, disease, are all going to dictate different timelines on all of these processes. How damaged is your pancreas? How damaged is your stomach and intestinal tract? And so on. Your muscles may become quite efficient at using free fatty acids and ketones while your pancreas remains on the diabetes spectrum. It can take time for beta cells to calm down, regenerate. The complexity of these multiple processes come to the fore more completely when you look at just how complex ketogenesis is. The fact remains, the ketogenic diet works for so many things we can’t quite get a handle on the multivariate mechanisms of action in it. Most of the mechansims are not just complex, they seem, with our limited knowledge, contradictory.

Let’s take appetite control for example.

Most of us who have even dabbled in keto have experienced its appetite suppressing effects. It is part of its popularity: the reduction in appetite makes the formerly impossible task of dieting much easier to take on. It’s one thing to use will power and careful calorie counting to lose weight. It’s quite another when you suddenly have no desire to eat and can go long intervals between meals without even a second thought. It’s empowering.

Clinically, however, the hard-core scientific evidence lags behind. An interesting review of the existing literature on ketogenic diet and its food intake and appetite effects was published in February. The existing literature is sparse and low power, but what data exists supports the anecdotal experience of low appetite. However, we personally have also experienced some “fat-adapted” patients, with good blood glucose control that also experience hunger. Anecdotally, it appears on the discussion boards in the ketoverse all the time.

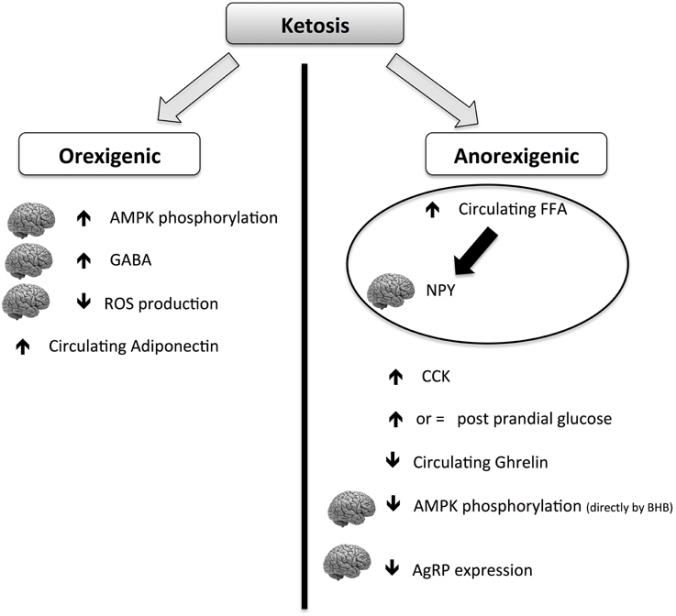

The above chart from the review being discussed here shows that keto diets have a paradoxical ability to cause both hunger and appetite suppression, though the net effect seems to be appetite suppression. It does seem to explain some mechanisms by which it could make some people feel MORE hungry.

Additionally,we have hypothesized that there is a tipping point in ketone production that can bring on an insulinergic effect. People commonly confuse “ketosis” with “ketoacidosis” (this is what is behind the horrified look of some health professionals when you mention you are practicing and/or prescribing the ketogenic diet–often, they don’t know the difference). DKA–diabetic ketoacidosis–only occurs in type 1 diabetics. It can occur rarely in type 2 diabetics who have progressed so far in their disease that they are now both type 1 and type 2 diabetics at the same time. It is important to understand that DKA can only occur in an extremely low or negative insulin environment because the way we regulate ketones in the body normally is through insulin release. So, think of the subject who prior to the ketogenic diet was on her way to type 2 diabetes. Her increased body mass and her constant high glucose stimulated the production of insulin producing beta cells in the pancreas. Once on keto, a high level of ketones, particularly if they are being artificially raised with excessive mct consumption, all of those beta cells go to work on lowering the ketones with surges of insulin. The pancreas does not down-regulate as quickly as the body loses fat mass and gains insulin sensitive tissues in its place. It certainly cannot down regulate as quickly as the blood glucose drops to around 85 or below on a steady basis, which happens in some keto dieters in a matter of days. In this time there might be overproduction of insulin that causes hunger, fatigue, thirst, and irritability. This will certainly adjust on its own, but there could be some interventions including increased exercise and some insulin-sensitivity inducing medications that could assist during the adaptation period. Subjects during this period may also find it difficult to lose weight and might retain water. This is part of the pancreatic adaptation period, which in those who were previously type 2 diabetic or on the road to it, may experience it. This may also occur later in the process for those subjects who were previously on diabetes meds and they are slowly withdrawn.

Returning to this review, it also thoroughly discusses other possible (likely?) mechanism for reduced food intake on the ketogenic diet including the ever popular gut biome thesis and the underexplored neuro-endocrine juncture. Of particular interest is the discussion of GABA and glutamine–because this is connected to the well-known anti-convulsant properties of the ketogenic diet (often low GABA is associated with seizure activity). No true conclusions are reached because these orexogenic and anorexigenic hormones and peptides are paradoxical. Insulin signals satiety—except when too much of it causes hunger, for example. Fascinating and maddeningly complex.

We do know, however, that the regulation of food intake is key to not just initial weight loss but maintaining that weight loss and the consequent health benefits long term. We similarly know that this regulation occurs between a lengthy conversation between the brain, adipose tissue, and the so-called “second brain” in the gut. It seems to be the cause of a lot of misunderstanding between the obese and the usually non-obese medical and health and fitness community that attempts to assist them. There is just a different conversation going on in a body that reaches a tipping point of adiposity than in one that remains below that threshold. This is key to thinking of compassionate and effective ways to help the obese.

via Ketosis, ketogenic diet and food intake control: a complex relation… – PubMed – NCBI.